What does make people switch? What is it that makes someone change their mind or their behaviour? These are crucial questions to any marketer and particularly baffling to the business-to-business marketer. This is because we b2b marketers operate in a world complicated by the multi-faceted decision making unit comprising buyers, technicians, management policy setters and so on – all who claim to make their decisions rationally. This white paper offers thoughts on b2b switching behaviour and the forces that shape these decisions.

The starting point for our understanding of “what would make them switch” is to recognize that there are different groups of people with different needs in our target audience. It would be an unusual situation for everyone to be motivated by the same things. Of course, this presupposes that we have an understanding of our market and know how customer groups differ in terms of meaningfully different needs.

Our understanding of the different needs of customers helps us begin to work out what would change a “buyer’s” mindset. In other words, we can expect someone who says that they are driven by quality to have their head turned by a quality product, or someone who is paranoid about their source of supply to be attracted by a strong brand that they can trust. However, these are broad brush views and things are not as simple as that.

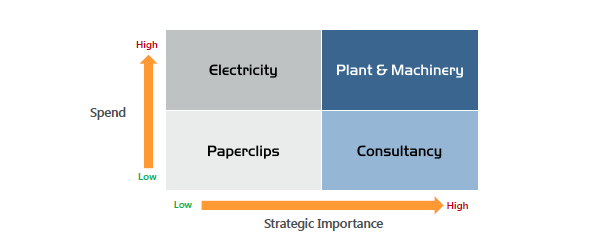

In our search for what drives behaviour in business-to-business environments, let’s look at four classically different segments. Most people reading this white paper will work with a company that supplies functional products (or services) – products that are bought because they are needed to facilitate the production of some other goods or services down the value chain. These functional goods can be located in one of the quadrants in the following diagram (Figure 1 below).

In the south-west corner is the “paper clip” quadrant representing products that are of low value and that are not strategic to the buying company’s future. In the north-west corner is the “electricity” quadrant, representing undifferentiated products where the annual spend may be quite high but the supplier could be any one of a number of reputable companies who are not embraced as strategic partners by the buying company.

The “consultancy” box in the south-east of the matrix represents an interesting group, as here we have suppliers who may not dominate the purchase ledger but who certainly have a strong strategic input into the future success of the purchasing organisation.

Finally, we have the plant and machinery group in the north-east quadrant. This box typically includes suppliers of products and services such as plant and machinery that are strategically vital products to the companies that operate them and for whom they account for a substantial amount of their costs.

The behaviour of “buyers” in each of these segments can be expected to be very different. The buyers of paper clips operate at a relatively low level within a company, delegated to buy bits and pieces of office equipment to ensure that the business functions smoothly.

The buyer of paper clips does not want to be embarrassed by paper clips that break. Also, they want someone they can trust to provide the cornucopia of office supplies needed to run a modern office – a one-stop-shop. But frankly, they may not know too much about paper clips and how they are made. Indeed, they may not care what type of steel they are made from or the quality of their finish. They may be more influenced by the care and attention given by the sales person who calls regularly and remembers their birthday with a bunch of flowers.

Contrast this with the buyer of “electricity”. This is the commodity box where the products on the shopping list account for a substantial expenditure but where there is very little differentiation in the buyer’s eyes between suppliers. Products in this box are always subject to price pressure as this is the most obvious lever that prompts switching. In fact, it is a box of opportunity where the clever marketer can explore customers’ needs and add services that create a “lock-in”. Of course, in this quadrant there will be companies that buy entirely on price but a surprisingly large proportion will be happy to consider paying more for stock management, emergency deliveries, and technical service support.

Moving on, the companies that supply strategically important products or services are generally regarded as specialists and as a result, there may be considerable loyalty to a supplier. In this box, the brand of the supplier is likely to be important, especially if they have a reputation in a field. Personal relationships are also a major influence. This is very much the “who you know” and reputation quadrant.

Finally, companies buying products and services that account for a significant spend and that are also strategically important are reluctant to switch to another supplier. A switch may take place but only after careful consideration of the consequences of the move. Airlines do move to new suppliers of aircraft but they have to carefully weigh up the effect on spares management, maintenance, crew training and customer preferences.

What themes emerge from this examination of switching behaviour for different types of products and services? The first thing we note is that both rational and emotional factors weave their way into all the decisions. The problem we face is that buyers and specifiers in industry find it hard to admit to or even work out the influence of the emotional effect.

Market researchers attempt to measure these influences at different levels. There is the very obvious “front of mind” level where a buyer or specifier is asked very simply to say why they choose a supplier or what would prompt them to switch. Not surprisingly, because it is front of mind, the answers are fairly predictable. “We choose the best quality for the best price and of course delivery is important”.

The researcher may follow this with a prompted question that reminds the buyer or specifier what issues are in the equation. This memory jogger may identify new factors. There are many variants on the prompted questioning theme. For example, the respondent may be asked to rank factors, score them out of 5 or 10, or spend points over half a dozen factors to indicate which carries the most weight.

Figure 2 – A Simple Points Spend Question To Establish Customer Needs

I would now like to get some measure of how you would choose a supplier of LPG. I would like you to imagine you have 100 points to spend on issues concerning a supplier of LPG. How would you allocate these points between the following:

| Attribute | Points Spend |

|---|---|

| Product quality /performance | |

| Product availability and delivery | |

| Price | |

| Customer ordering | |

| Technical and sales support from the supplier | |

| Environmental issues | |

| Reputation and brand of the supplier | |

| TOTAL (Must add up to 100) | 100 |

More sophisticated tools such as conjoint analysis can show the trade off between different issues although even here there is no guarantee that the emotional issues will be given their full weight.

Points spend and conjoint use structured market research interviews to throw light on the forces shaping behaviour. On their own they are not enough to give us the deeper insights of how buyers behave and what makes them switch. For this we have to turn to qualitative research. And here we must get as close to psychology as we can to get a deep understanding of what makes buyers tick.

Let’s consider for a minute the mind of the general public in our search for how emotions affect buying decisions. Take the car buying public. Can we really say why we switched from that practical estate to a 4X4 off-roader to take the kids to school? For sure the question gets rationalised – “we have a steep drive and it can be difficult to get out of in the snow” (yes, on the one day a year that it does snow!); or “I feel safe in it with the kids” (yes, even though the stability is less than for most conventional saloons). In general we recognize more readily these emotional pulls and tugs in other people than we do in our rational selves.

Now you may argue that the rational b2b buying community does not get side-tracked by this mumbo jumbo. Somebody buying for a company is expected to use their professional skills to make the decision and most of this will be influenced by the facts.

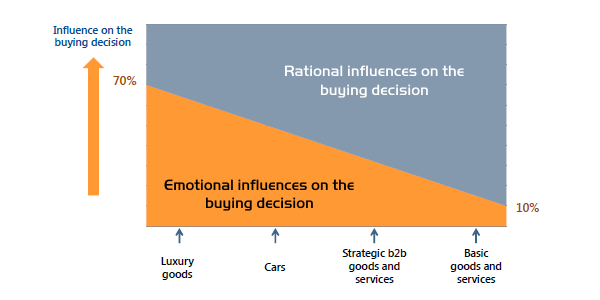

Maybe so, but company buyers and specifiers do not leave their emotions at home when they set out for work. Figure 3 gives a stylized indication of how the emotional factors change in importance between consumer goods and industrial goods – but even in the most mundane of industrial products, emotions are known to play their part, often accounting for 10% or more of the buying decision.

One further issue we should consider before we move on is the difference in views of buyers compared to specifiers and technical people. In general the former put more emphasis on price and the latter more on quality and technical service. There could be differences in views between small companies and large companies. Companies at an early stage in their life cycle may think very differently to those in a more mature phase. Companies in developing countries sometimes think differently to those in developed countries.

This discussion is leading us to a point where we can build a check list of factors that prompt switching:

Switching more readily takes place when:

- The product is a commodity supported by very few services

- There is no strong relationship between the buying company and the seller

- Products and services are easily interchangeable with little or no testing/prequalification

- The product or service is not supported by a strong brand

- A market is awakened by a new supplier or an energetic supplier who runs a campaign that talks about the benefits of buying a different product or service

- The buying company has switched a number of times and has no fears of the difficulties of switching again

- The product or service is not of strategic relevance to the buying company

- The financial benefits of switching to a different product or service are considerable.

Conclusion

Once we have won a new account, our aim should be to make sure that from now on there is as little switching as possible. We conclude the white paper with three important ways to generate loyalty – in other words, stopping switching:

Build a strong brand

A definition of a strong brand is one that people insist on to the exclusion of all others. A strong corporate or product brand is a great means of creating loyalty and stopping switching. A key to strong branding is to build on and emphasise values that have a strong relevance to the market and which are not the high ground of competitors.

Build interlocking relationships

Strong corporate brands involve far more than the promotion of company names, logos and value statements. They are strengthened enormously by the relationships built up between the selling company’s sales and technical teams and the buying company’s purchasing and specifying staff. It will be hard to dislodge the sales person handing out doughnuts and coffee to a customer’s production staff as they arrive at 6.30am. If that same person then works his or her way through the company checking that everything is hunky dory with supplies and quality they will find it very, very hard to switch.

Segment your customers by needs

We conclude this white paper where we came in. At the end of the day, all marketing is about segmentation; namely understanding and responding to the different needs of customers. With this understanding it will be possible to create different customer value propositions that meet those needs more closely and so resonate with customers better than a vanilla offer for everyone.